By Threat Intelligence Team

This article aims to present relevant information about the workings of financially motivated cybercriminal groups operating in the Ransomware-as-a-Service model, which coordinates attacks against public and private institutions with the cooperation of partner teams referred to as affiliates.

Technical characteristics of malicious software (malware) and tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) observed in intrusions will therefore not be covered in this analysis.

The information contained in this report was gathered over months of research, in which Tempest’s Cyber Threat Intelligence team gained access to affiliate panels of ransomware groups including ALPHV (aka BlackCat, aka Noberus). Therefore, this report has two versions: the “Private” version, which has already been released internally to our clients on our Threat Intelligence platform; and this “Public” version (TLP:CLEAR), which has a wider reach, with the purpose of sharing information that may be useful to cyber defense teams, executives, regulators, legislators and other parties in the public or private spheres interested in a more detailed understanding and fight against this type of threat.

In the article entitled “Stealers, access sales and ransomware: supply chain and business models in cybercrime“, published in June 2022 on SideChannel (Tempest’s blog), we wrote about different business models in cybercrime, their relationships and how each service provided contributes to nurturing a supply chain that can lead to incidents with major impacts, such as simple extortion and double extortion. These services include: Phishing-as-a-Service, Malware-as-a-Service, Access-as-a-Service, among others.

Ransomware-as-a-Service is a business model similar to SaaS (Software-as-a-Service), which consists in a group that provides ransomware to criminals who gain unauthorized access to corporate networks and encrypt the data in these environments, usually causing unavailability of the systems. As a result, the victim is extorted with the promise of having their environment restored after paying the ransom; in addition, some groups promise to inform the victim about vulnerabilities and security flaws exploited in the network so that the company can fix the compromised environment. In case the victim pays the ransom, the amount of money received is shared among criminals from the group that supplied the ransomware and the threat actor who used it.

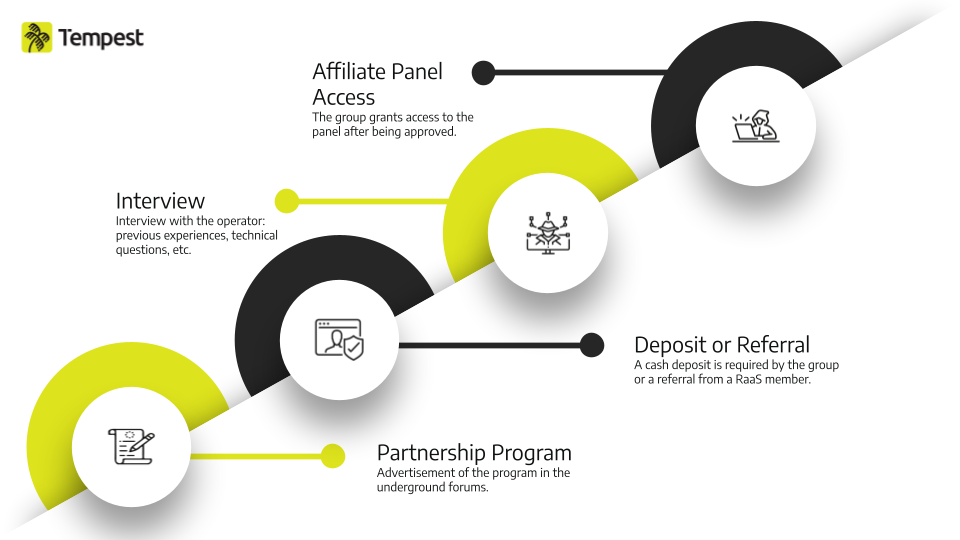

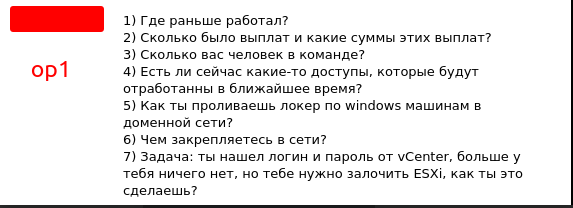

Usually, the ransomware is not supplied separately to the threat actor who intends to use it, but as part of a service platform that includes other functionalities. We’ll talk about these platforms later. As a way of stimulating the cybercrime economy and guaranteeing their profits, many of the groups that control ransomware are open to partnerships and commonly advertise recruitment campaigns known as “Partnership Program”; the underground forums XSS, eXploit and, specially, RAMP, are the most commonly used for this purpose.

Partnership Program

In order to attract future partners, such as pentesters and IABs (Initial Access Brokers), the publications consist of a detailed technical description of the ransomware’s characteristics, such as encryption algorithm and compatible operating systems; information on available resources including panels used to configure and generate the ransomware; as well as payment terms based on the ransom amount. Due to the large number of competitors, ransomware groups try to provide a variety of benefits to attract more and more partners and decrease the chances that current members will leave these groups.

Although large Ransomware-as-a-Service operations, such as LockBit and ALPHV, are well-structured and have administrators with a high level of maturity, cybercriminal groups tend to be volatile and surrounded by uncertainty. Therefore, the managers of these operations are usually concerned with ensuring the satisfaction of their team members and partners, in order to maintain a relatively solid operation and, consequently, obtain greater financial gains and reduce the chances of information leaks, as already observed in groups such as Babuk, LockBit and Conti.

Source: Tempest

Interviews & Affiliates

After advertising on forums, the recruitment process can take place in different ways. Groups such as 8BASE, Knight and Medusa adopt simpler and more straightforward processes, with fewer steps to prove skills, knowledge or possession of data exfiltrated from victims.

However, we noticed that some groups such as LockBit, ALPHV (BlackCat) and NoEscape (a possible rebrand of Avaddon ransomware) have a much more rigorous process, requiring initial deposits for non-Russian speakers, a vouch from other criminals and an interview with some questions, including technical ones. Although partnership programs are advertised on forums, the recruitment usually goes through a private channel, usually via TOX.

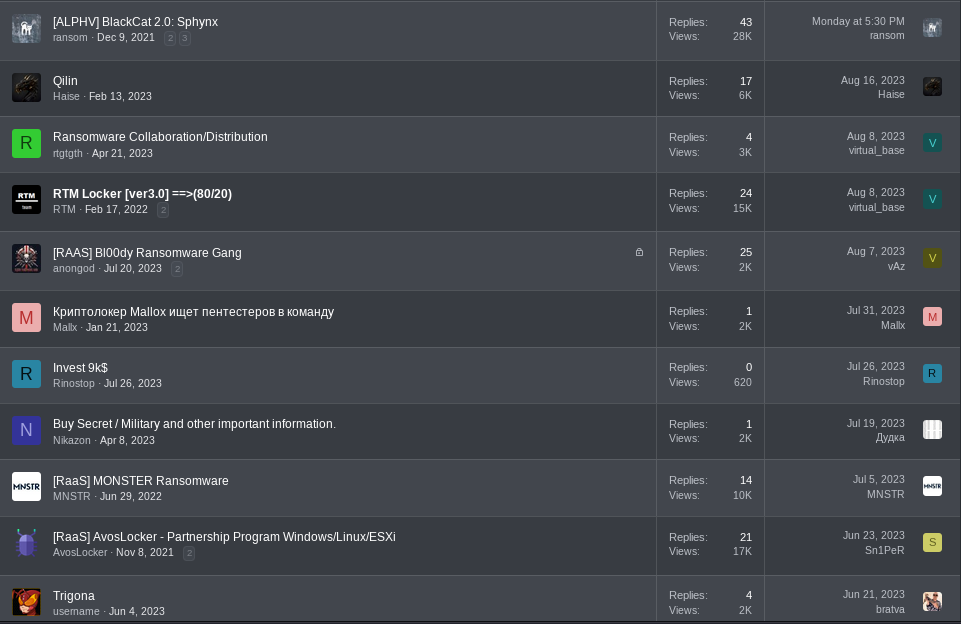

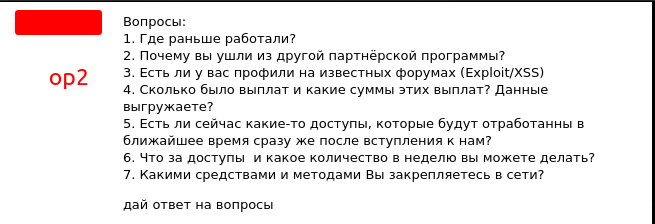

Below are some questions asked by the operators of two major ransomware operations to a group of affiliates during some of these interviews. We’ll call these groups Operator 1 and Operator 2, or Op1 and Op2 for short.

Some questions are asked by both operators, Op1 and Op2, while others are asked exclusively by one of them:

- Op1 and Op2: Where did you work previously?

- Op1 and Op2: How many payments were made and the total received?

- Op2: Why did you leave the other partnership program?

- Op2: Do you have profiles on known forums (Exploit/XSS)?

- Op1: How many people are in your team?

- Op1 and Op2: Are there any access that will be worked on after joining us?

- Op2: What types of access and how many do you get per week?

- Op1 and Op2: How do you gain initial access to the networks?

- Op1: How do you spread ransomware on Windows machines in a network with Active Directory?

- Op1: Challenge – you’ve found username/password of a vCenter, there’s nothing else, but you need to encrypt an ESXi, how do you do that?

Source: Tempest

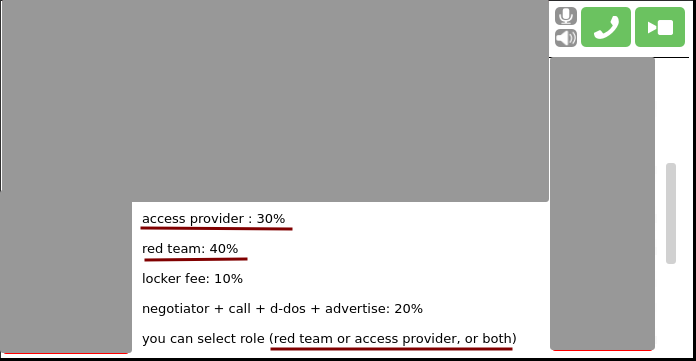

Once approved, after this and other stages, the partner team and its members are then considered affiliates, also known as adverts. In some Ransomware-as-a-Service operations there are two types of affiliates: access providers (IAB) or pentesters; and they therefore have different payment conditions.

Below is a screenshot showing the payment conditions for affiliates of another ransomware group, which we’ll call Operator 3.

Source: Tempest

We can therefore understand affiliates as individuals or subgroups responsible for conducting intrusions into corporate networks, using as part of their arsenal resources made available by one or more ransomware operations to which they may be linked. Thus, when we refer to tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) from an incident authored by LockBit, for example, we are actually referring to TTPs of affiliates, who used the LockBit malware to encrypt the data, as well as other resources from this operation. Among some affiliates, we highlight Wazawaka linked to the former Babuk ransomware and other ransomware operations, and the “National Hazard Agency” group, which was run by Bassterlord, a LockBit affiliate.

From build to extortion: how affiliate panels work

Of the resources provided by ransomware operations, the affiliate panel is a tool responsible for giving autonomy to the configuration and generation of the ransomware, disclosing and negotiating with victims (called clients), receiving ransom payments and cryptocurrency transactions and other features.

Below, we’ll detail the main features of the ALPHV operation’s affiliate panel.

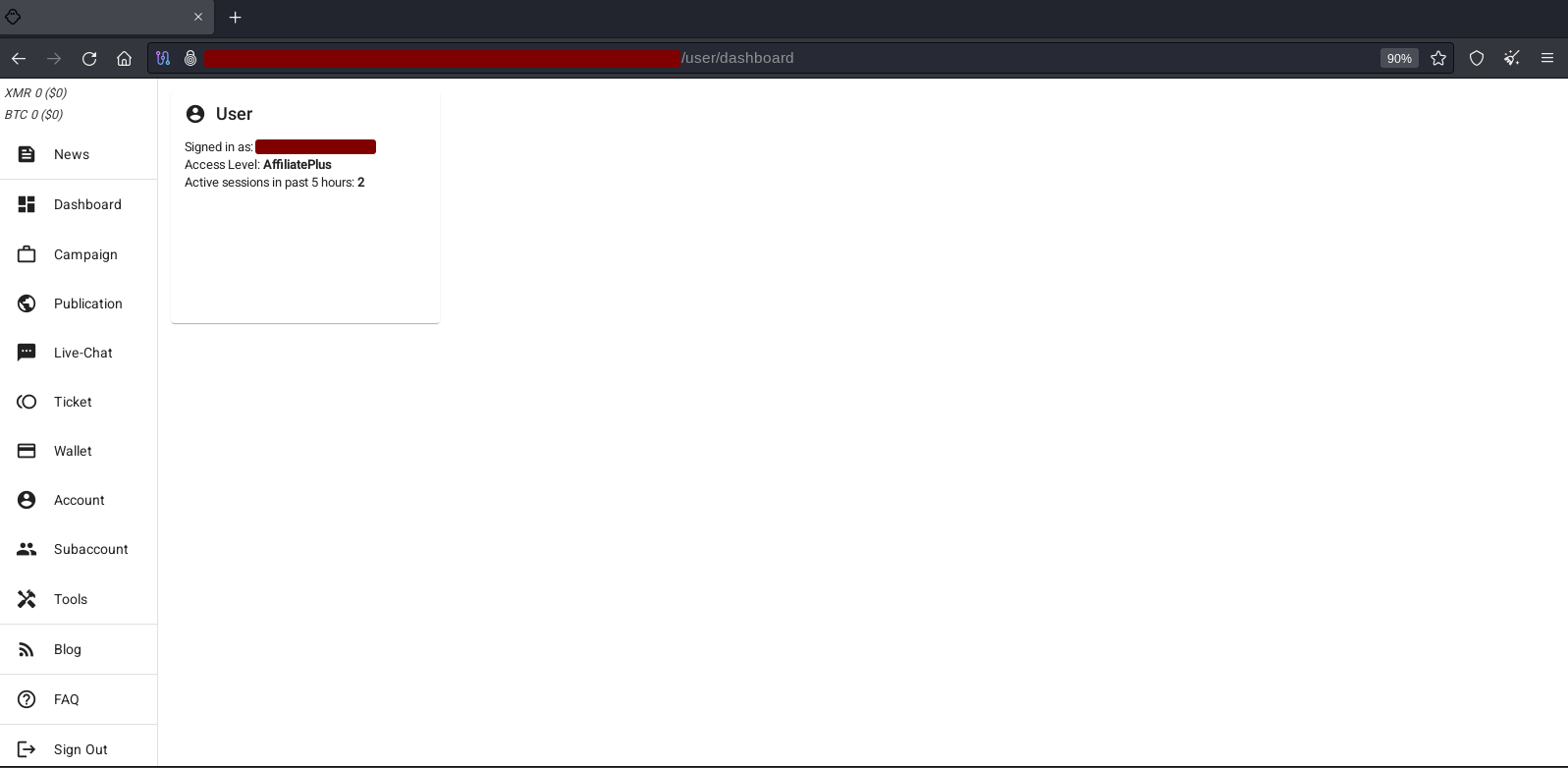

ALPHV (aka BlackCat aka Noberus) Dashboard

Each affiliate has a unique “.onion” address to access the panel and, in some cases, different levels of access. ALPHV used 3 favicons, of which the ghost icon in the browser tab in the image below is an indicator of the affiliate panel. After receiving a total of 1 million dollars in ransom, the affiliate will have access to three features: Bruteforce Request (hash), DDoS Request and Call Request. On the home screen, we see information about the type of access “Access Level: AffiliatePlus“, which is related to an account with access to all the platform’s features.

Source: Tempest

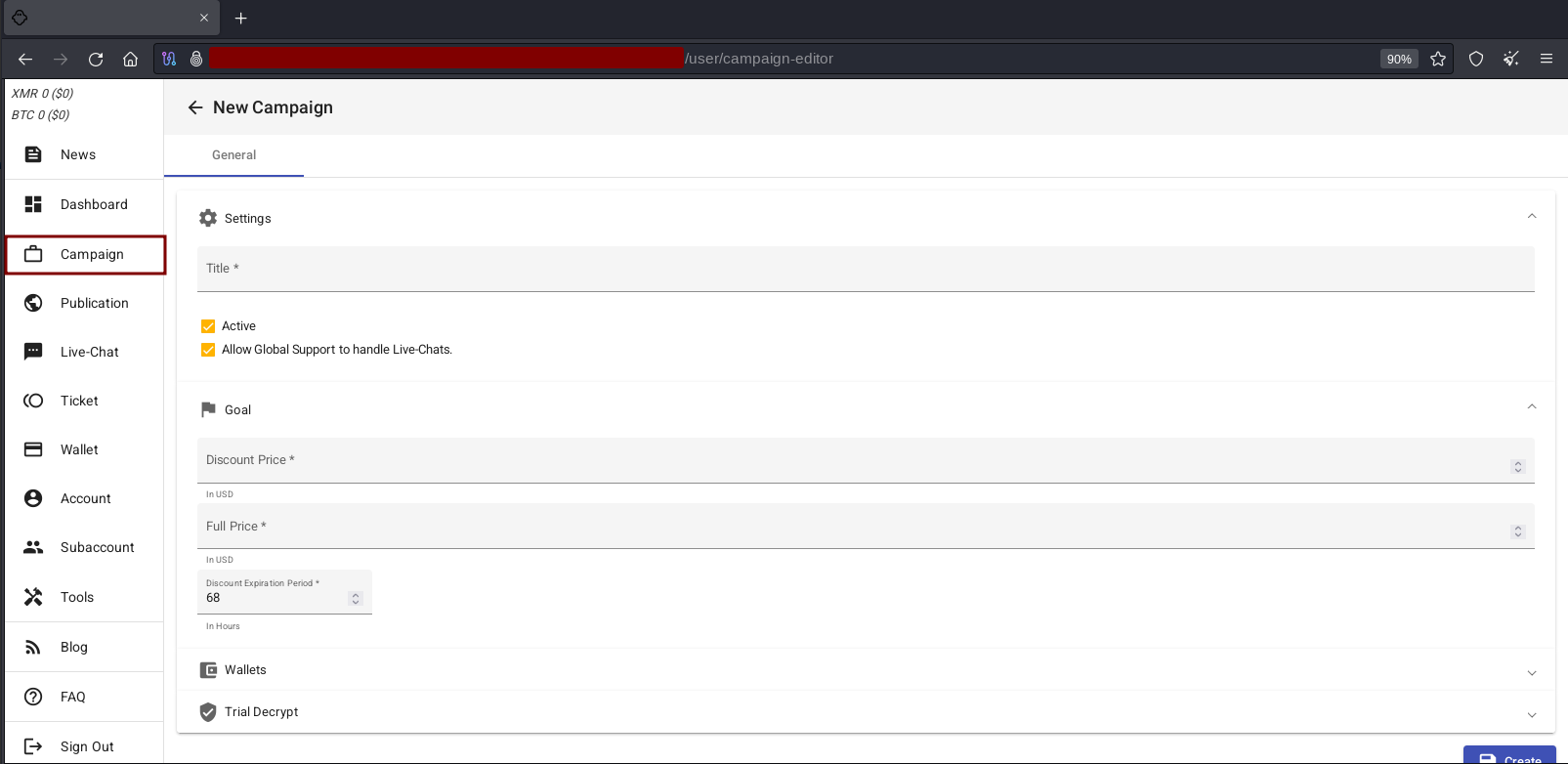

“Campaign” and “New Campaign” sections

The “Campaign” section allows the affiliate to manage all their targets and create new ones. Each new target is registered by the affiliate via the “New Campaign” option.

This section contains the following fields:

- Title: title of the campaign, i.e. the name of the target company;

- Active: enable or disable the target. The option can be used to indicate ongoing or finalized negotiations;

- Allow Global Support to handle Live-Chats: determines whether the negotiation via chat with the victim will be done only by the affiliate (not selected) or any member of the operation (selected);

- Discount Price: discount of the ransom granted to the victim in case payment is made on time;

- Full Price: the full amount of the ransom after the end of the deadline;

- Discount Expiration Period: expiration period of the discount of the ransom (defined in hours);

- Wallet: address of the Monero or Bitcoin wallet used to receive the ransom. A different address is used for each victim;

- Trial Decrypt: determines the number of times the victim can perform trial decrypts, i.e. decrypt data from the compromised environment.

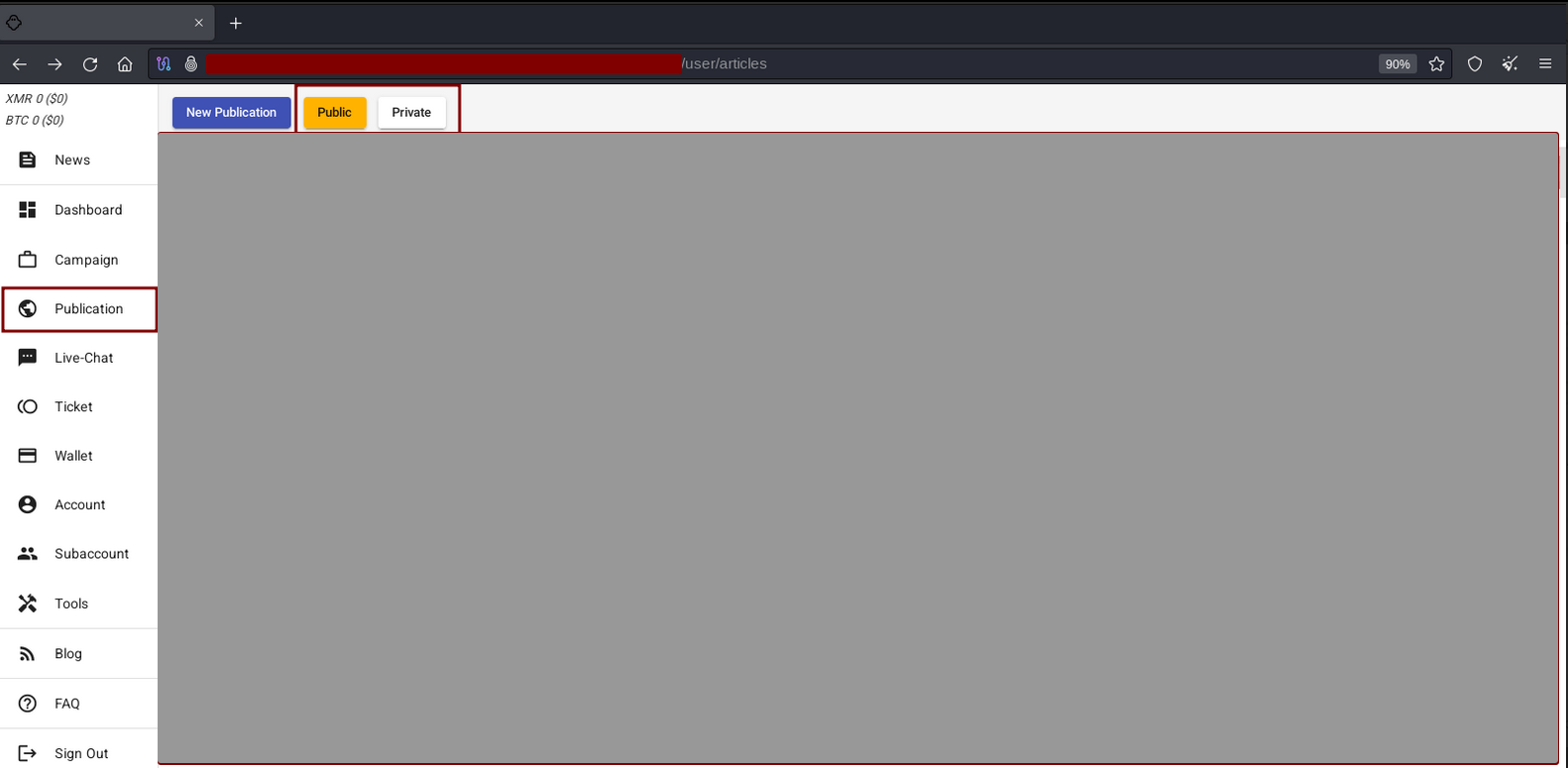

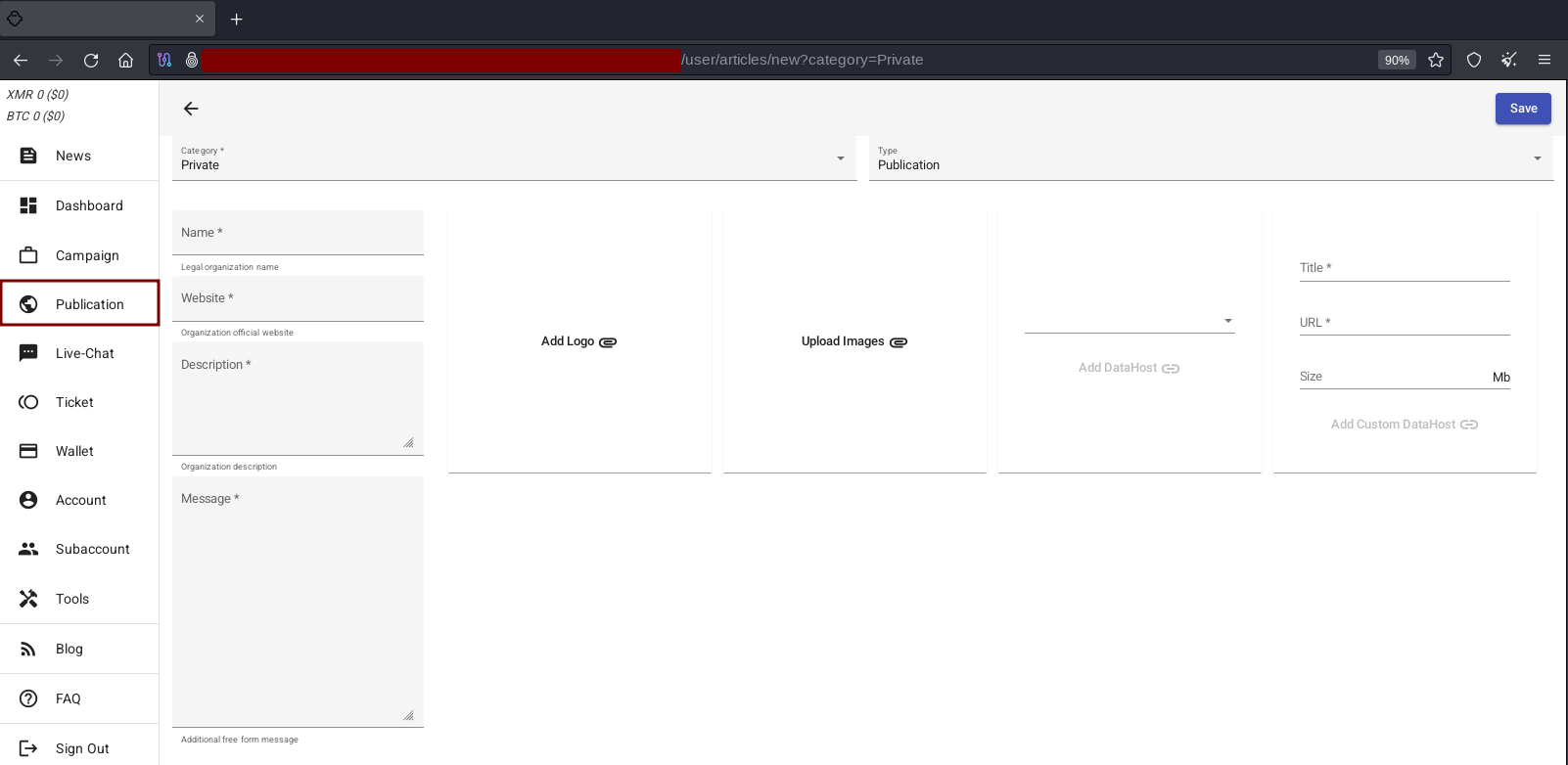

“Publication” and “New Publication” sections

Typical of Double Extortion attacks, after encryption and eventual exfiltration of data, the information regarding the victim will be disclosed on Data Leak Sites (DLS), websites run by ransomware operations for extortion purposes. The disclosure of the victim company and data leakage are also actions carried out by the affiliate as a way of pressuring the victim into paying the ransom demanded by the criminals. However, we noticed that there is the possibility of making an internal publication (Private), where the victim’s information (such as the victim’s name, samples and other details) will not be disclosed on the group’s DLS and therefore will not be publicly accessible on the Internet; this is the default publication mode, and can be used by the affiliate in the beginning of a negotiation. In this way, we can understand that the companies that were already disclosed on Data Leak Sites do not reflect the total number of victims of a ransomware operation.

The Publication section allows the affiliate to create new publications (New Publication) and view all the victims already publicly disclosed on the group’s Data Leak Site. We noticed that in addition to the date and time, the affiliate has visibility of the number of visits made to a victim’s disclosure. This information allows them to measure the degree of visibility and public interest in their victims and can be used to negotiate ransom payments.

Source: Tempest

Under Publication -> New Publication, the affiliate configures the publications and from the options and fields available, there can seen the type and category (Private and Public) and fields relating to information on the leaked data (URL and Size).

Source: Tempest

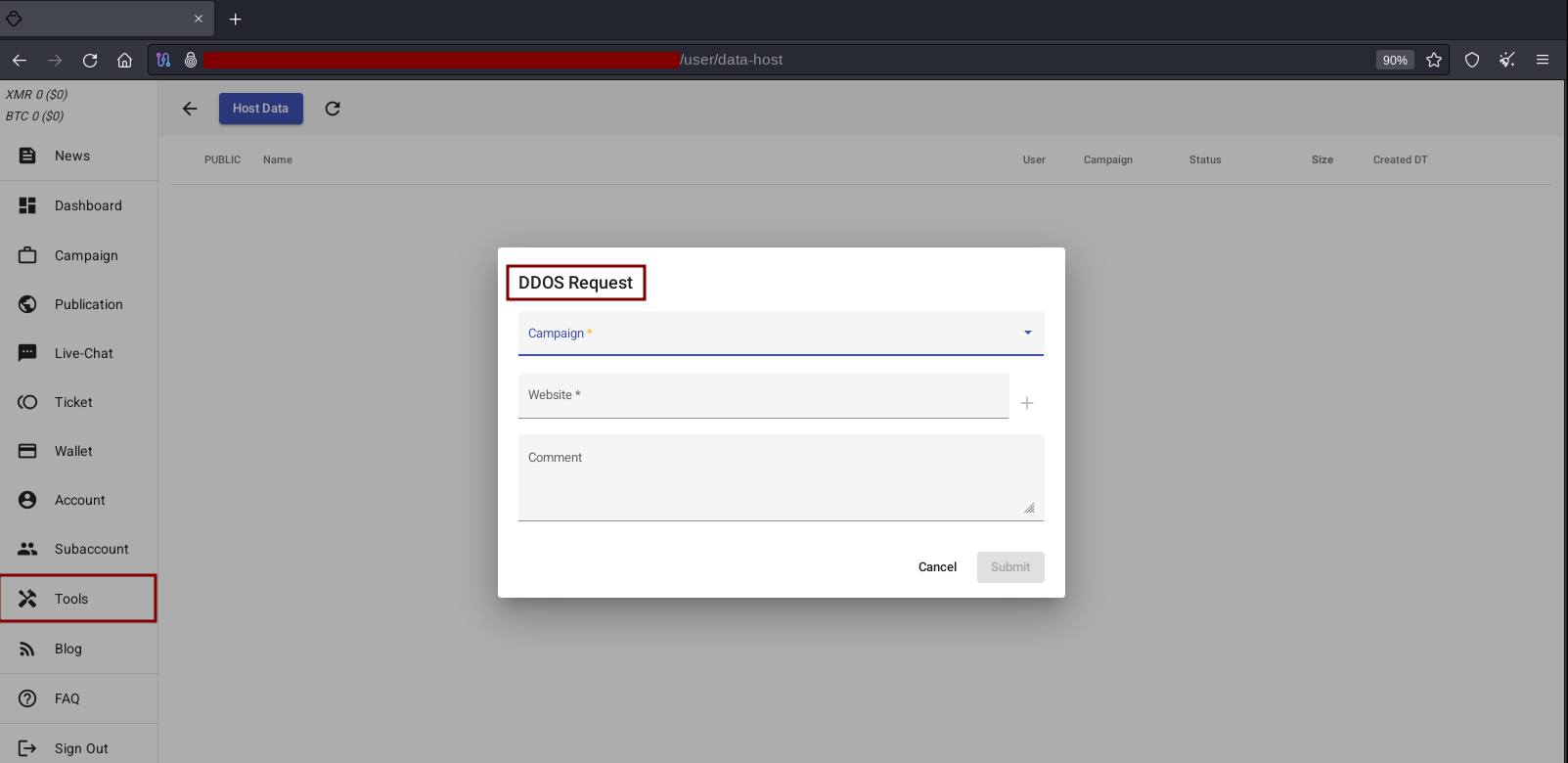

“Capability” and “Triple Extortion” sections

In addition to the basic features presented previously, which are common in affiliate panels of other operations, ALPHV provides to “Affiliate Plus” tools that can assist in the post-exploitation process, negotiate with the victim or even carry out distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. During the investigation, we observed that ransomware operations such as Medusa, NoEscape, LockBit and ALPHV provide or intend to implement tools in their panels for conducting DDoS attacks (T1498).

DDoS Request

In addition to the stress naturally inflicted on the victim by having to deal with the effects of breach and unavailability of the corporate infrastructure, ransomware operations aim to further psychologically destabilize their victims through different forms of threats.

On the technological side, in addition to encryption and the threat of disclosure and leakage of their victims’ data, DDoS attacks and other methods can be used as a third extortion factor (Triple Extortion). These attacks aim to cause the unavailability of public-facing services in order to put even more pressure on the affected companies to pay ransoms.

Source: Tempest

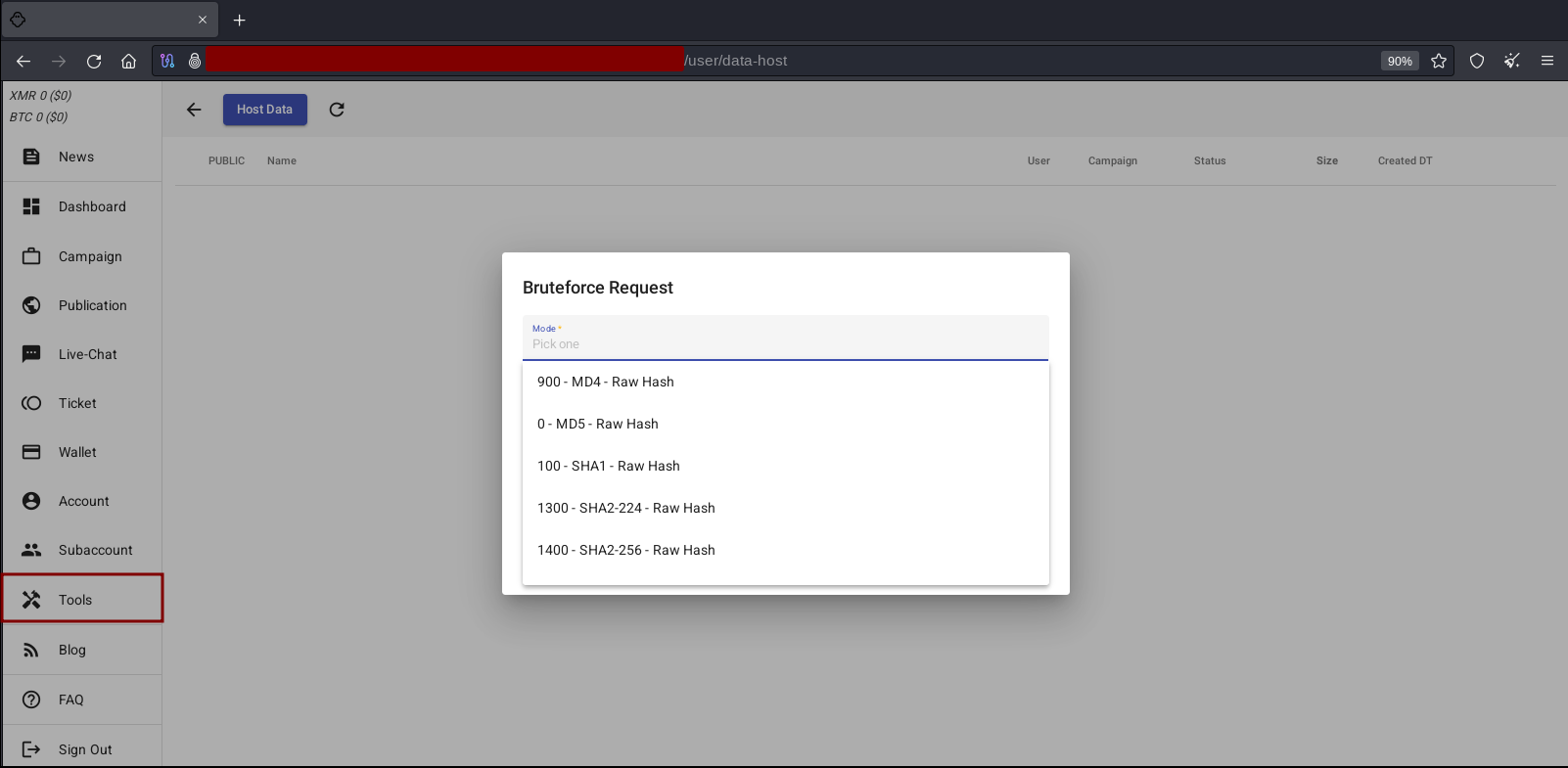

Bruteforce Request

From the techniques commonly present in TTPs of ransomware incidents, we observed that LSASS Dump (T1003.001) is often used in the privilege escalation phase (TA0004) of the attack chain. The technique aims to obtain data from Windows users, such as a plaintext password, NTLM hash and Kerberos ticket, in order to gain access to accounts with administrative privileges or different permissions, with the aim of carrying out lateral movement (TA0008) and other post-exploitation activities.

The hashes retrieved through the LSASS dump and other techniques can be used in attacks known as Pass the Hash (T1550.002), Pass the Ticket (T1550.003), OverPass the Hash and others, where the authentication process takes place using hashes and other data instead of the user’s password. However, in a scenario where the use of these techniques is not possible due to issues related to the victim’s environment or the adversary’s lack of technical knowledge, criminals often bruteforce hashes (compare hashes), which can be performed through websites such as cmd5, tools or services on underground forums known as “Hash Cracking”.

We identified the Bruteforce Request feature available to ALPHV affiliates, which aims to “bruteforce” various types of hashes to gain access to systems and user accounts in order to exfiltrate data, escalate privileges, move laterally or evade defense mechanisms. At the time of access, we observed that this ransomware operation had a database of hashes, including 399 different types, including Kerberos, NetNTLM, AES, MD5, SHA, ChaCha20 and several others.

Source: Tempest

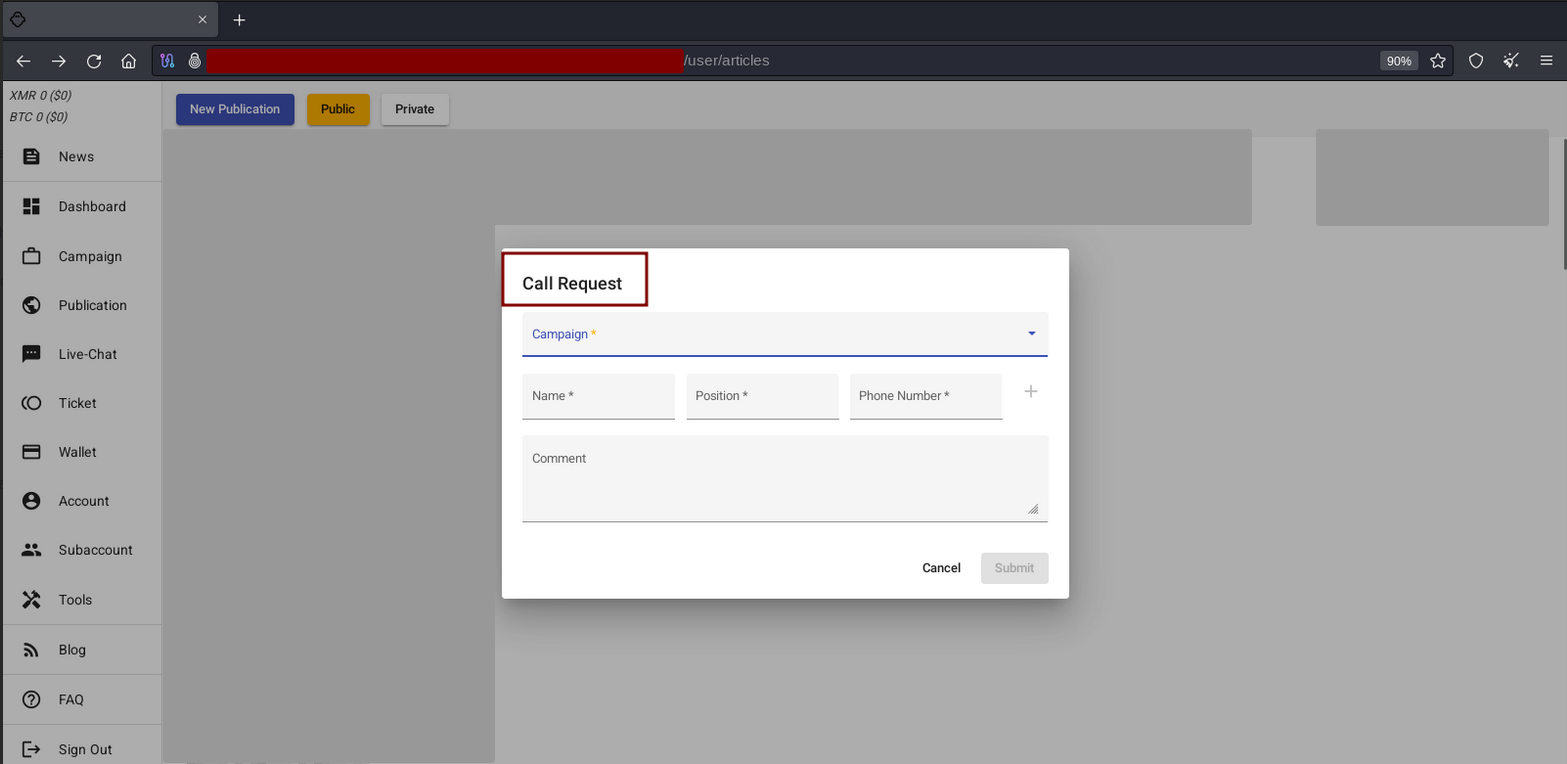

Call Request

We have noticed that the Call Request feature, which allows the affiliate to contact the victim by phone, is a common feature on other operations’ panels. However, although we have not tested this feature, we believe that it could be used to threaten victims, conduct negotiations or even be used to obtain user information through social engineering.

Source: Tempest

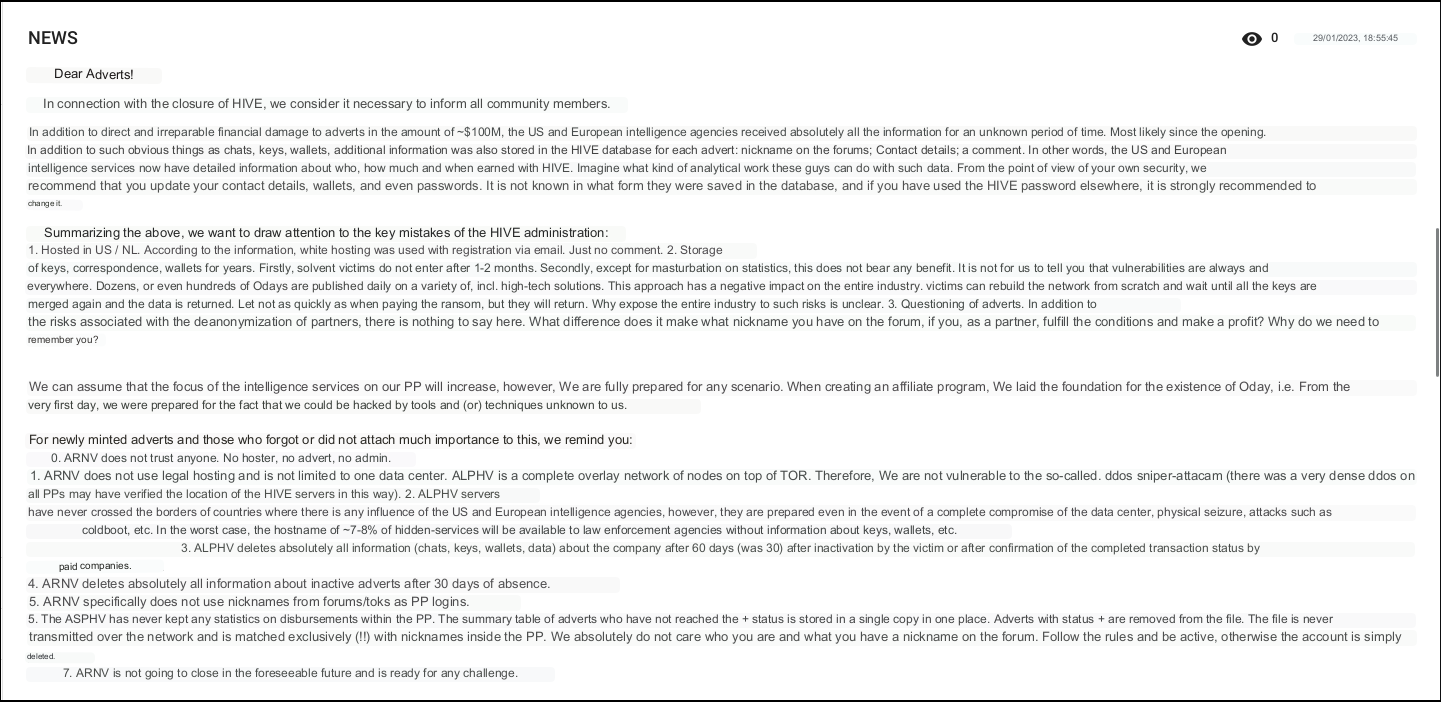

“News” section

In the News section, we identified at least 5 publications made by the group’s operators between June 2022 and December 2023 regarding version updates and new features of the ransomware, information about the infrastructure used by the group, unavailability issues, as well as guidance for its affiliates on OPSEC and operational security.

Due to the number of images, we won’t present all the screenshots. Therefore we will highlight by text the most relevant information observed in all the updates carried out by ALPHV operators. The images were generated from an automatic Google translation from Russian to English, so there may be some inconsistencies.

Timeline of relevant facts in chronological order:

- June 2022: release of 2 new features which allow the encryption process to be restarted once the first run has been completed. This is disabled by default, however, the “sleep-restart” and “sleep-restart-duration” options can be configured during the build (configuration/generation) or used during the execution of the ransomware.

- July 2022: release of the ALPHV Collection. A platform that allows to search for files exfiltrated from their victims. The tool allows searches using wildcards (e.g. *.txt *.pdf), file names and text in PDF, DOCX and even image files such as JPG, PNG and others. The group claimed to have developed the platform in order to contribute to the cybercrime community, as well as to make an impact on their victims;

- November 2022: the group reports a problem with its infrastructure allegedly due to server configurations and updates. According to the operator, the problems would have caused 2 days of unavailability of the “Live-chats” service used by affiliates to negotiate with victims;

- January 2023: following the infrastructure outage and shutdown of the Hive ransomware, ALPHV operators published a post advising their affiliates to update their passwords, cryptocurrency wallets and contact information. In addition, the operators commented on Hive’s main mistakes that led to the end of its activities, as well as infrastructure characteristics and organizational issues of ALPHV’s operation (image below);

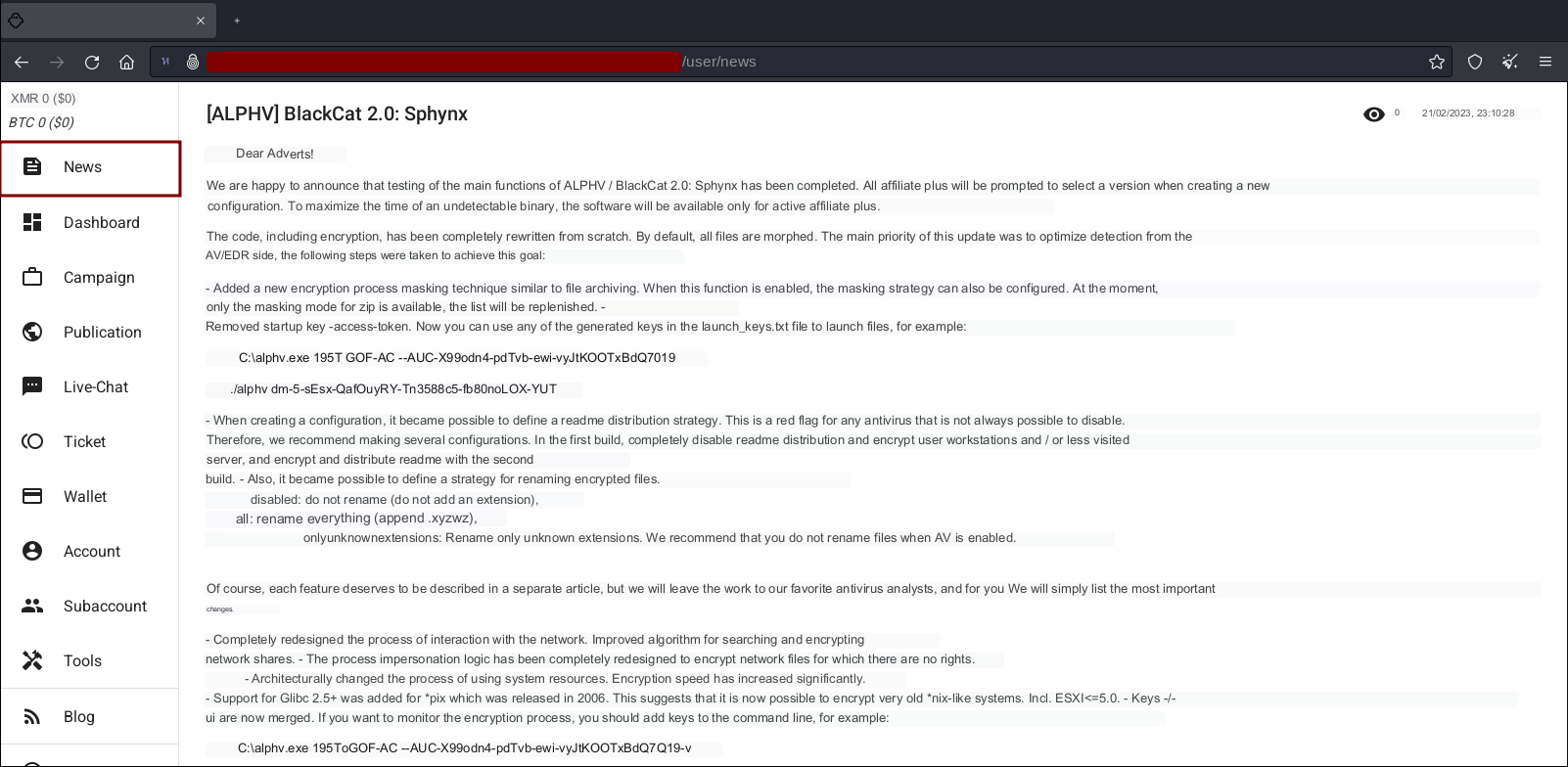

- February 2023: disclosure of a new ransomware variant named “Sphynx” and future updates. Details will be discussed below.

- December 2023: operators report infrastructure problems causing servers to be unavailable. However, this is said to be related to a police operation that allowed the FBI to gain partial access to the ALPHV infrastructure. Despite this, the operation remained active for some time.

ALPHV / BlackCat 2.0 (Sphynx)

- One of the improvements aims to mask the encryption process by simulating file compression. ZIP mode supported when enabled.

- Allows the use of any token. In order to execute the ransomware, it is necessary to inform the token generated when creating the build in the affiliate panel as an argument.

- Behavior change for renaming encrypted files. “disable“: does not rename, i.e. does not add an extension to the encrypted file, “all“: renames all files, “onlyunknownextensions“: renames only unknown extensions (not recommended to rename files with antivirus enabled).

- Improvements to the search algorithm and encryption of network shares;

- Improved impersonation process for encrypting network drivers where the threat actor does not have access permission.

- Glibc 2.5+ support for Unix-like systems released after 2006. The feature enables encryption of older Unix-like systems. Ex:. ESXi 5.0.

- “-v” verbose option. By default, the ransomware runs in the background.

- Option “-ui” allows the use of a graphical interface;

- “readme” file with distribution strategy can be delivered in txt, QR-code, sgv and png;

- In future versions, it will be possible to use all the “Impacket” functionalities during infection (atexec, psexec, etc.), as well as using PtH (Pass-The-Hash) techniques for impersonation, distribution and encryption of network drivers via SMB.

In a Microsoft publication on August 17, 2023, the company reported a new version of the BlackCat ransomware (ALPHV) which was using the Impacket tool to spread the ransomware in the environment, as well as the impersonation techniques mentioned above, such as the use of compromised credentials when creating the build (ransomware) in the affiliate panel.

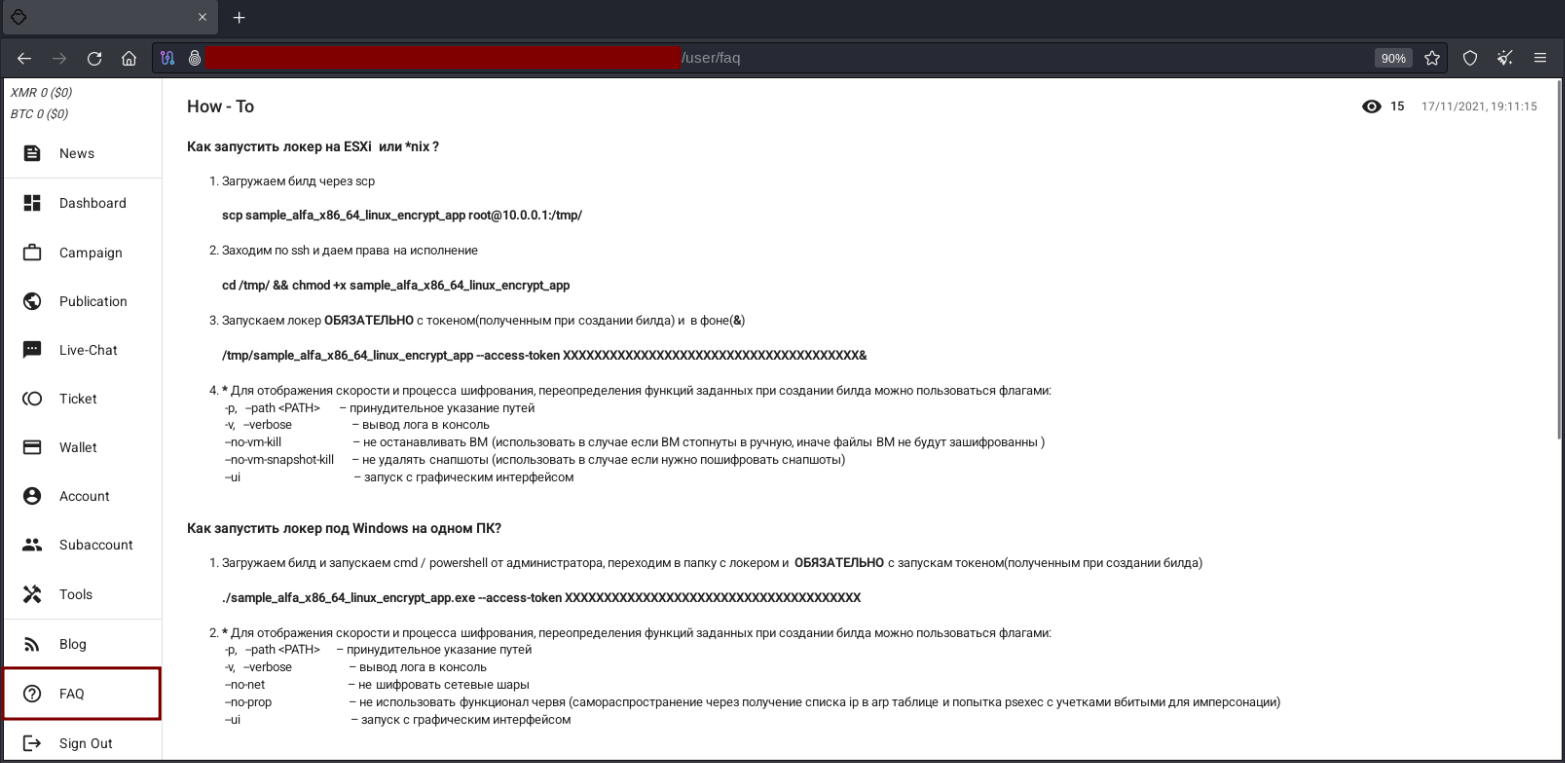

FAQ & How To

In the FAQ section we found some guidelines for running the ransomware on Linux and Windows operating systems. However, although the last publication took place in November 2021 about this topic, we have identified some relevant points related to the execution and dissemination of the ransomware via Active Directory.

How to run the locker for Windows on the entire domain (Active Directory)?

- Upload the locker (ransomware) to the domain controller and run cmd or Powershell with administrative privileges. Then copy the locker to the “C:\WINDOWS\sysvol\sysvol*yourdomain*\scripts\locker.exe” directory;

- The locker must necessarily be available via the Windows share through “\\yourdomain\netlogon\locker.exe”;

- Edit “Default Group Policy” or create a new group policy and set it as the default;

- Select “Computer” -> “User Configuration” -> “Preferences” -> “Control Panel Settings” -> “Scheduled Tasks”;

- When creating a new scheduled task, fill in the fields and set it to run with SYSTEM user privileges. In the “Actions” tab, configure as follows:

-

- Action → Start a program

- Program/script → cmd.exe

- Add as argument “/c \\yourdomain\netlogon\locker.exe –access-token XXXXXXXXX”

- After saving the settings, run the command “gpupdate /force” from the domain controller.

Source: Tempest

Conclusion

From this analysis, we have observed some similarities among different ransomware operations. In addition to the similarities of the affiliate panels, we have seen that even the questions asked during recruitment and how the operations work are relatively similar. Although these groups refer to other ransomware operations as “competitors“, we believe that these similarities are due to the fact that criminals are involved in different groups and, on a certain level, there is information sharing among those who make up the Ransomware-as-a-Service ecosystem.

In addition, as is evident from the Hive ransomware publication by the ALPHV operators, affiliates can be involved in different ransomware operations. Thus, it is possible for the same group of affiliates linked to more than one group to conduct intrusions with relatively similar TTPs, but using ransomware from different families; as observed by the threat actor Tropical Scorpius, who is said to be involved with Cuba ransomware and Industrial Spy. Furthermore, it is possible that the opposite could happen, i.e. different affiliates have similar TTPs because they use techniques and tools provided by different ransomware operations. Therefore, regardless of who carried out the attack, it is essential for defense teams to focus on the behavior of tools, malware and techniques used by adversaries, since indicators (IoC and IoA) are perishable.

During our investigation, we observed the interest of ALPHV operators in obtaining resources to exploit a particular vulnerability in Fortinet devices, which could indicate that their affiliates would not be able to exploit this type of vulnerability due to the level of complexity. Thus, we can infer that Ransomware-as-a-Service operations depend on their affiliates to gain access to corporate networks and consequently for financial gain. Therefore, we can conclude that the level of sophistication, i.e. the ability of a group to carry out intrusions, is directly related to the capabilities and knowledge of its affiliates.

Finally, we highlight the importance not only of correctly implementing MFA mechanisms, avoiding the use of resources such as SMS, but also of drawing up password policies, so as to reduce the chances of passwords being discovered in Brute Force attacks and of credentials stolen by criminals or possibly leaked being reused by threat actors. In addition, we suggest updating and configuring Windows in order to mitigate the use of Pass the Hash and Pass the Ticket techniques, which are commonly used by threat actors during the post-exploitation process, as well as being implemented in an automated way by some ransomware for dissemination on the network.

Additionally, since we have observed that ransomware operations have in their arsenal the ability to carry out DDoS attacks, we suggest implementing Anti-DDoS systems and checking critical services that are unnecessarily exposed on the internet.

End of ALPHV (BlackCat)?

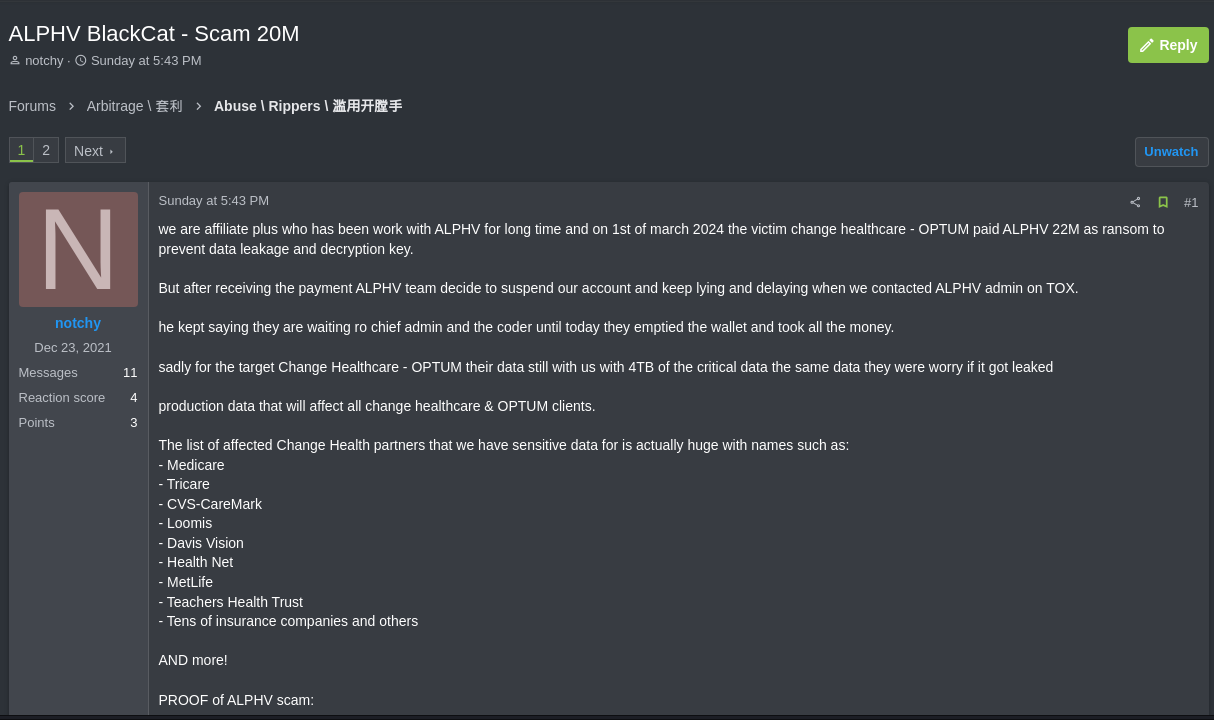

On March 3, 2024, an alleged ALPHV affiliate identified as “notchy” published information on the RAMP forum containing allegations that the payment received for extorting one of his victims, the North American company Change Healthcare, had been fully withdrawn by members of the operation, without sharing the amount of money with the affiliate. According to the Bitcoin wallet transactions reported in the publication, on March 1st the criminals received 350 BTC, the equivalent of approximately 22 million dollars. On March 3rd, seven transfers of 50 BTC and one of 0.211148 BTC were made, leaving the wallet empty.

Source: Tempest

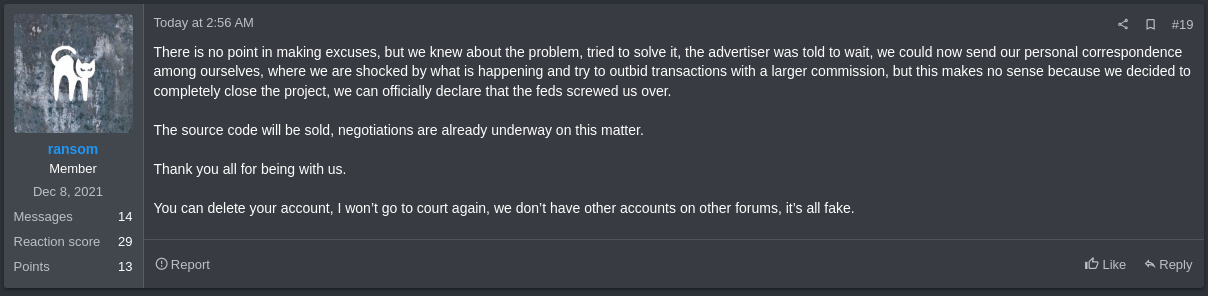

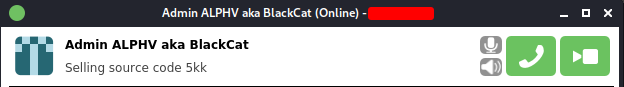

Later, on March 5th, the user “ransom” used by ALPHV officially announced, in the same post on the RAMP forum, the end of the project, claiming that the police operation conducted by the FBI and other entities had negatively impacted the group’s activities. The group’s operator has also announced the sale of its source code, which it claimed was being negotiated.

When a ransomware group decides to shut down a project, taking with it the amount of money that was supposed to be used to pay its affiliates or access providers, the term “exit scam” is used; an action carried out by ALPHV and operators of the NoEscape group in December 2023.

Source: Tempest

Source: Tempest

However, the fact that the project has allegedly been shutdown does not imply the end of the ransomware operation, which may eventually occur rebrands, i.e. the emergence of one or more new ransomware groups made up of criminals involved with ALPHV (aka BlackCat). Currently, all users of forums and ALPHV’s Tox platform account have been banned and are no longer used by the group.